The discovery of Saharan rock art

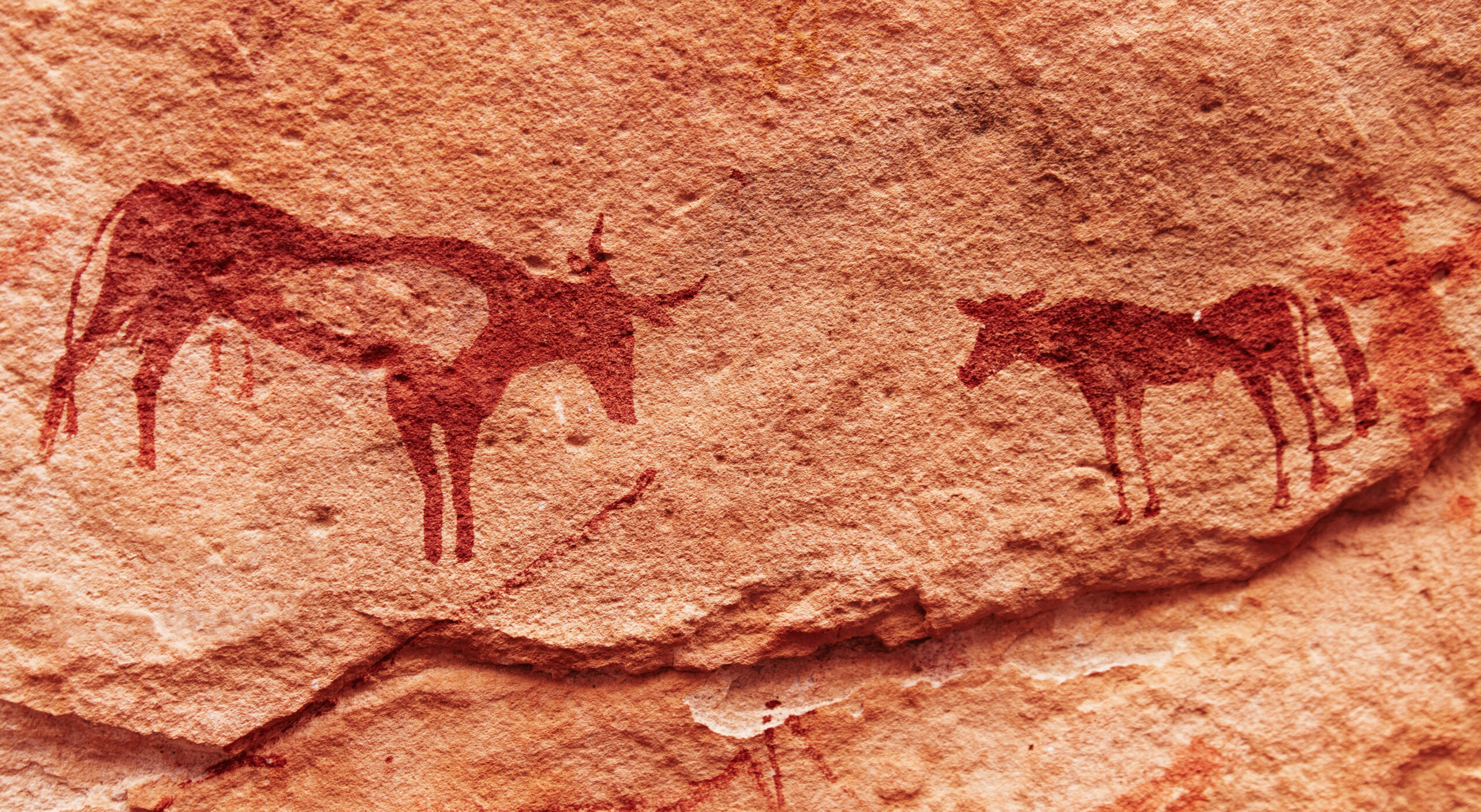

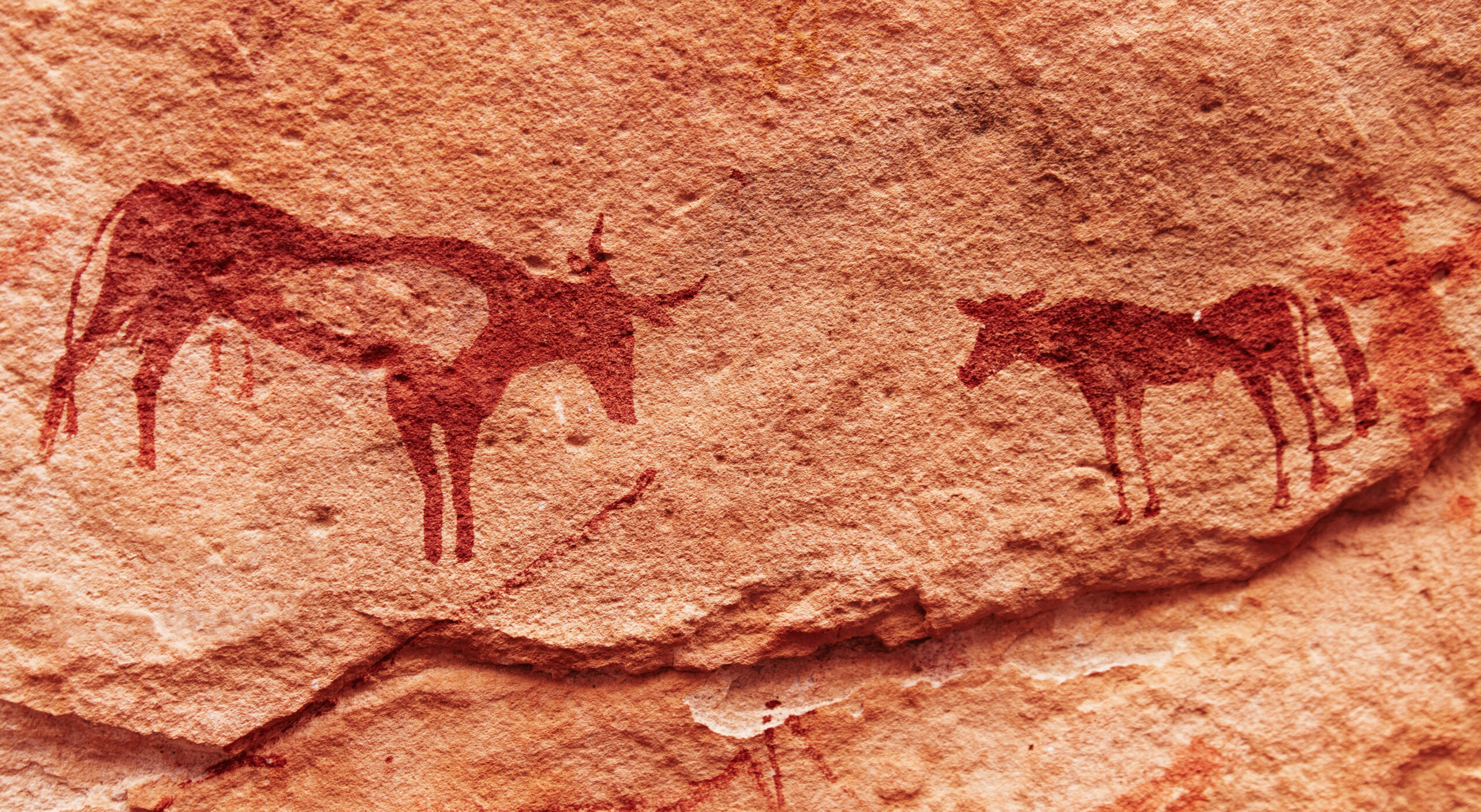

In the early 1930s, the French lieutenant Charles Brenans discovered rock paintings and engravings depicting numerous anthropomorphic figures and large animals from the African wild fauna. These turned out to be the oldest paintings in the Sahara.

In 1956, Swiss ethnologist Yolande Tschudi published the first monograph devoted to this art. In the same year, the French prehistorian Henri Lhote and a team of Tuaregs carried out a 15-month study campaign organised by the Musée de l’Homme in Paris, the CNRS and the Institut d’études sahariennes d’Algérie. He carried out extensive documentation work in the Tassili n’Ajjer.

On his return to Paris in 1957, he inaugurated an exhibition that was an immediate success and a great success. The paintings and engravings were brought to the attention of the general public by Henri Lhote, but unfortunately he was also the main person responsible for the deterioration of these discoveries. To date, researchers have been able to record more than 15,000 paintings, drawings and engravings made around 10,000 years ago, with a wide variety of subjects bearing witness to the peoples who lived in this region in prehistoric times. We can see all kinds of animals, humans, more or less human figures, weapons, chariots, scenes from everyday life (pastoralism, hunting, war, marriage, mating, etc.).